The Ultimate Guide to Choosing the Best Business Entity: LLC, S Corp, C Corp, and Beyond

Chris Daming, J.D., LL.M. : Oct. 14, 2024

Chris Daming, J.D., LL.M. : Oct. 14, 2024

We're guessing that at this point you’ve read dozens of blogs that regurgitate very similar “pros and cons” of LLC, S Corp, and C Corp. You've probably learned about LLCs being passthrough and being more informal; S Corps saving you money on self-employment taxes; and C Corps being dreaded because of “double taxation.”

What a lot of those things you read don’t say is that, in most cases, the choice doesn’t make a big difference initially.

Think of it like when you buy a new phone or Smart TV -- you probably don’t use 80% of the features it has because you don’t need them.

This guide takes a much different angle. Hopefully I’ll simplify it enough for you that you should feel pretty good about what makes sense for your business by the end.

We’ve broken it down into a 5-step process. And as a spoiler, in most cases:

- Some people should be a sole proprietor.

- Most people should form an LLC taxed as disregarded entity in their home state.

- Some people should form an LLC taxed as S Corp in their home state.

- A few people should form a Corporation taxed as C Corp in Delaware.

The rest of this guide will explain all that and help you figure out which choice is best for you. It'll take you about 25 minutes, but many people spend 15+ hours on this issue so it's well worth your time :)

One note: this guide assumes you already know you want to be a for-profit company. If you're still considering whether a nonprofit makes sense, learn more about nonprofit advantages and disadvantages first. Otherwise, let's go to Step 1.

Step 1: First, Understand Your Entity Choices

To really make the right choice, it's important to understand what the "choice" you're making actually is.

When you choose an entity, you make two choices. What will be what’s called your “state law” entity, and then what will be what’s called your “tax law” entity.

Every business in the US has both—a state law entity, and a tax law entity.

What's a State Law Entity?

Your state law entity effectively determines how you’ll operate. To form a “state law” entity, you file a document usually called either articles of organization (if an LLC) or articles of incorporation (if a corporation) with one state that you choose.

For almost every business, the state law entity choice is either an LLC or a corporation. Those are the most common for-profit choices. You can also choose to be a nonprofit corporation.

There are several other state-law entity choices depending on your state (e.g. limited liability partnership; limited liability limited partnership; limited partnership; L3C; B Corporation, among others). But in almost all cases, unless you have millions of dollars in assets, you'll almost always form as an LLC or a corporation.

What's a Tax Law Entity?

Your tax law entity determines how you’ll be taxed. This is how the IRS recognizes your business. There are only four types of tax law entities:

- Disregarded entity;

- Partnership (not to be confused with a “general partnership” or a “limited partnership”; this partnership just means the type of tax law entity that the IRS recognizes);

- C corporation;

- S corporation.

That’s it. Almost every formal company in the United States is either an LLC or a corporation. And literally every for-profit company in the United States is one of those four tax law entities. Almost every large company you’ve ever heard of is a corporation (state law entity) taxed as a C corporation (tax law entity). Most small businesses owned by a single-owner are an LLC (state law entity) taxed as a disregarded entity (tax law entity).

Recap of the Two Choices

So it goes like this (with some exceptions noted below):

First: Choose a State Law Entity:

- LLC; or

- Corporation

Second: Choose a Tax Law Entity:

- Disregarded entity;

- Partnership;

- C corporation; or

- S corporation.

Most publicly traded companies are: corporation (state choice) + C corporation (tax choice).

Most small businesses with one owner are: LLC (state choice) + Disregarded Entity (tax choice). We're intentionally repetitive -- it helps!

Think of the tax law entities as different sections of the IRS tax code. Disregarded entity is “disregarded” from the IRS tax code and included in individual income provisions. Partnership is Subchapter K. C corporation is Subchapter C. And S corporation is Subchapter S.

If you have a company, you must be one of the four tax entities (otherwise, how would the IRS get your money? 🙂).

State Law Entity, Meet Tax Law Entity

We said that the two main state law entities are LLC and corporation. If you have a state law entity, you must have a tax law entity (will say this a dozen times for emphasis).

Here’s how that works.

(One Owner) If you form an LLC as your state law entity and you have one owner, here are your options:

- Default: The IRS automatically says your tax law entity is a disregarded entity. If this is what you want, you don’t have to do anything additional with the IRS to be classified as a disregarded entity. You’ll simply report your business income and expenses on Schedule C to your personal income tax return.

- Other options: In this scenario, you can “elect” to be taxed as a C corporation or as an S corporation by the IRS.

To elect to be taxed as an S corporation, you simply file an IRS Form 2553 with the IRS after you have formed your LLC.

If you want to be taxed as a C corporation, you simply file an IRS Form 8832 with the IRS after you have formed your LLC. (note: we’ll explain in detail later, but almost no one who forms an LLC chooses to elect to be taxed as a C corporation).

In other words, an LLC with one owner can be taxed as:

- Disregarded entity (default);

- S corporation (can elect);

- C corporation (can elect but almost no one does - we'll cover this later).

What tax law entity is missing? Partnership. If you’re an LLC with one owner, you can’t choose to be taxed as a partnership. That requires at least two people. We’ll hit on that next.

(2+ Owners) If you form an LLC as your state law entity and you have more than one owner:

- Default. The IRS automatically says your tax entity is a partnership. If this is what you want, you don’t have to do anything additional with the IRS to be classified as a partnership.

- Other options. You can also elect to be taxed as either a C corporation or as an S corporation.

In other words, LLC with two or more owners can be taxed as:

- Partnership (default);

- S corporation (can elect);

- C corporation (can elect but almost no one does).

What tax law entity is missing? Disregarded entity. To be taxed as a disregarded entity, you can only have one owner.

And that’s everything for LLC choices. Next is corporations.

If you form a corporation as your state law entity (regardless of how many owners), your tax options are:

- Default: C corporation.

- Other Options: S corporation. You can elect to be taxed as an S corporation. (one caveat: you can’t have more than 100 shareholders and still be an S corporation)

That’s it. You have those two options. If you form a corporation, you can’t elect to be taxed as a disregarded entity or a partnership. Why not? No idea. It’s just the law that the IRS enforces.

So, Now You Have a Couple Choices to Make. Your Two Choices Will Be One of These Options:

If a business has one owner, you have five choices:

- LLC + Disregarded Entity;

- LLC + C corporation;

- LLC + S corporation;

- Corporation + C corporation; and

- Corporation + S corporation.

And one other choice that we'll cover in Step 2 (sole proprietorship taxed as disregarded entity).

If a business has multiple owners, you also have five choices:

- LLC + Partnership;

- LLC + C corporation;

- LLC + S corporation;

- Corporation + C corporation; and

- Corporation + S corporation.

So, you really only have five options. There are lots of other weird entities that exist (limited partnership; limited liability limited partnership; etc.) but almost no one without an extraordinarily unique situation chooses those.

Let's go to the next step.

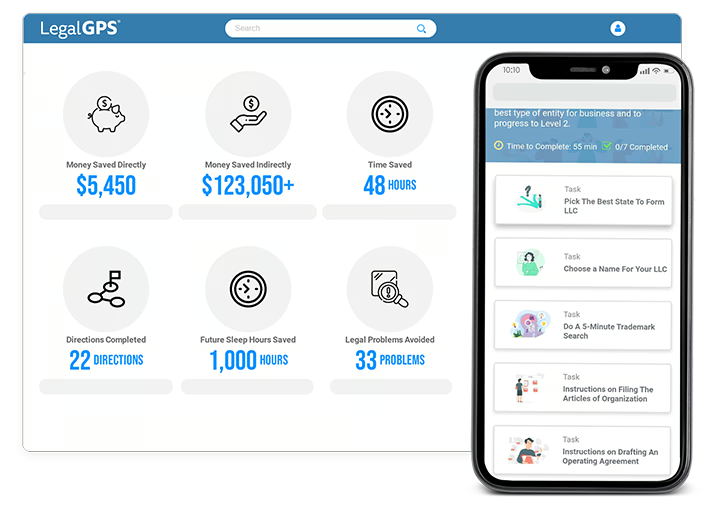

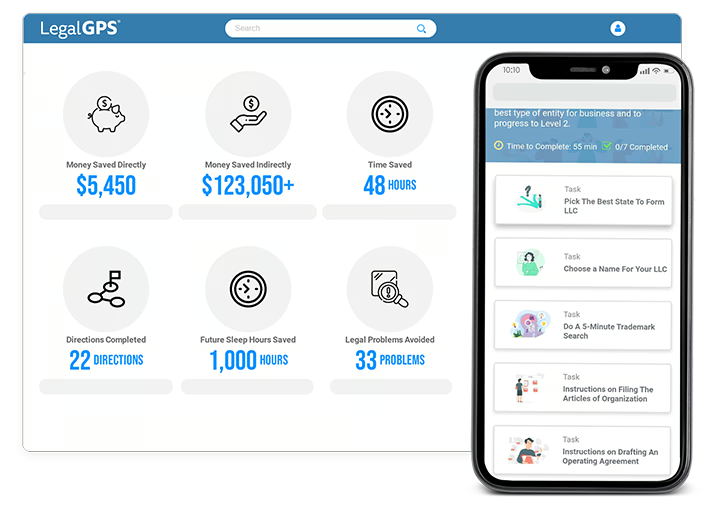

Legal GPS Subscription

Protect your business with our complete legal subscription service, designed by top startup attorneys.

- ✅ Complete Legal Toolkit

- ✅ 100+ Editable Contracts

- ✅ Affordable Legal Guidance

- ✅ Custom Legal Status Report

Step 2: Should you form an entity at all?

Before we dive into which of those choices make the most sense, let's first confirm if you even need to form a "formal entity" at all. If you're the sole owner and you don't form any formal entity, you're automatically considered a sole proprietorship in the eyes of the government.

Note: Skip to Step 3 if you already know you want to form an LLC or corporation and just aren't sure which one.

First ask yourself, does your business have potential liability issues?

One caveat -- entities do NOT provide liability protection when you commit a tort, which means you took or did not take an action that injures someone else. If your employee or other owner committed a tort, then it provides protection for you. But if you personally harm someone, you’re still liable for that harm (this is where insurance is valuable).

So how does "liability protection" help? For single-owner businesses without employees, it usually helps with contracts -- if you sign a contract on behalf of your LLC or corporation and breach it, the other typically can only sue the business, not you.

It's a much bigger help for multiple-owner businesses or businesses that have employees. In those situations, if the other owner or an owner does something that causes them to get sued, then the person suing can't try to sue you personally -- which helps you preserve your personal assets.

Next, how much does your state charge for forming/running an LLC or corporation?

Depending on your state’s fees (find them out here), sometimes remaining that way can save you money. For states like Missouri, for example, it only costs $50 one time to setup an LLC, so it rarely makes sense to remain a sole proprietorship because the alternative is so cheap.

|

Example Let’s say you moonlight as an artist and sell occasional paintings on Etsy. You generate approximately $2,000 in revenue each year. And you’re the only owner and you have no employees. If your state charges you $500 to form an LLC or a corporation, and you have to pay another $500 each year as an annual fee, then setting up an entity probably doesn’t make as much sense. |

But for other states that charge a high fee like $500 and an annual recurring fee, sole proprietorships could make more sense if the business has low risk, no employees, and other factors.

There are other factors and if you're still on the fence, explore our Sole Proprietorship vs. LLC guide for a deeper dive.

Step 3: Determine if Your Company is More Like a "Business" or a "Scalable Startup."

In most cases, your type of business likely dictates (1) what state law entity is best; (2) what tax law entity is best; and (3) what state is best for you to form your entity in.

We know that the word "startup" is often applied to every type of business (many people use it to mean every new type of business). But for purposes of helping you pick the right entity, we're only using it to apply to very small amount of businesses.

What we need is for you to identify whether your business fits more closely our guide's definition of "Business" or "Scalable Startup." And to give you a hint -- probably 99% of businesses should identify as a "Business" here.

If you're wondering why this matters -- the reason is that in a very few select cases, it makes more sense for a Scalable Startup to form a Corporation taxed as a C Corp in Delaware. For Businesses, rarely does either of those choices make sense. So, let's figure out which option best suits your scenario.

Option A: Scalable Startup

We define scalable startup as a scalable business that typically seeks venture capital and pays equity compensation (meaning you’ll pay people, in part, by providing a portion of ownership of your company) to at least it's initial founders and employees. While there are 30+ million small businesses in the U.S., there are less than 100,000 startups.

Scalable means -- generally speaking, it can grow exponentially without needing a lot of extra staff.

Option B: Business

You should identify as a business for purposes of Steps 4 & 5 in this guide if it’s any other type of business, like freelancers, restaurants, home-based businesses, or service-based businesses that aren’t scalable.

For additional guidance, Small Business is most likely your category if any of these apply: (1) you don’t plan on hiring employees (and even if you do, Small Business still probably applies, but see the next factors); (2) you don’t intend to seek investment or venture capital; (3) you don’t plan to issue equity compensation to pay your team - tech startups will hire employees and as part of the compensation package, they offer them partial ownership of the company, but this is rare for most businesses; (4) your business is service-based; or (5) you’re a freelancer.

If in Doubt, Choose "Option B: Business"

For some business owners, you might not be sure what’s the right category because maybe you’re closer to a Business now but eventually will turn into a startup. The best tip is to think about what your current company plans are. If things change dramatically in the future, chances are that you’ll just start a new company and form a new entity or convert your existing one.

|

Example |

This is exactly what our company did -- we started as an LLC in our home state. And when we grew and began seeking investment and paying equity compensation to new employees, we converted our LLC in a Delaware C Corporation. This way, we initially were able to take advantage of losses against other income with the LLC. But were able to be more prepared for investors and be able to pay equity compensation in a much simpler way by converting to the corporation.

Step 3 Recap

If you know your company is a Business, continue to the next step. If you're one of the 1 percent of companies that fit the "Startup" definition, check out Best State and Tax Entities for Startups.

Step 4: Pick your State & Tax Entity for your Business

Okay, we're getting close! Now that you've indicated you're company is closer to a "Business" than a "Startup" (as we define them). Let's analyze what state law and tax entity might be best for you in this two-part process.

One note: this analysis is catered toward single-owner businesses. While it mostly applies to all Businesses, multiple-owner businesses sometimes have nuances that require a much more in-depth analysis and should likely hire an attorney (reason explained here).

So, here we go:

Part 1: Choose a State Law Entity

While your state-law entity choices for a single-owner Business are LLC or corporation, more businesses in this category choose LLC.

But first a full disclosure: for most single-owner businesses in the " Business" category (which is most businesses in general), it doesn't make much of a difference. If you have a LOT of money and are putting a LOT of money into your business initially, then consider hiring a CPA and tax attorney to weigh all the pros/cons.

But -- thinking about the 80/20 rule -- only about 20% of the differences between LLCs and corporation matter for 80% of businesses. And those differences are relatively simple. (For a deeper dive, learn more about LLCs v Corporations).

Why do LLCs have a slight edge?

So, factoring all that in, why do LLCs have a slight edge?

LLCs are easier to form and operate.

They’re easier and faster to form and require less ongoing corporate formalities that are required by corporations. With corporations, you’re supposed to hold annual shareholder meetings, elect a board of directors, have regular board meetings, elect corporate officers, and pass resolutions, among other things.

If you’re a corporation, you have to file additional tax paperwork. (We’re assuming that no one in this small business category will be a C corporation, so we’ll only cover S corporation here.)

If you’re an S corporation, among other things, for taxes you have to file:

- Form 1120S - S corporation tax return. This is for informational purposes for the IRS, not how you pay tax, since being an S corporation makes you a pass-through entity.

- Schedule K-1, Shareholder’s Share of Income, Deductions, Credits, Etc. S corporations use this schedule to report to each person who was a shareholder at any time during the S corporation's tax year (and to the IRS).

- But also, even if you’re the only owner, the IRS will consider you to be an employee of your company, so you’ll have to file the employer forms (even if you’re the only “employee” and owner). You’ll also have to pay State Taxes, even if you don’t have any other employees.

LLCs often can have the same or better liability protection.

Limited liability companies do have a couple of true advantages when it comes to limitation of liability. They make it easier to "preserve the corporate veil" (this is a fancy way of saying, "If I preserve the corporate veil and I get sued, the suing party can't go after my personal assets), because you don't have to do "corporate formalities" like you do with corporations. And they also have charging order protection.

But Factor in Fees...

But, before you make your decision, it’s worth balancing the slight advantage LLCs have versus whether they could cost you any extra fees. For many states, LLCs are the same or less in fees than corporations and are less of a hassle. But for some states, the fees are substantially higher for LLCs (California in particular) and so if you’re a hobby business, LLCs might not make sense.

You can find out your state's LLC fees using this neat widget.

If you see that an LLC makes sense, then you need to figure out if you should elect S corporation as your tax choice of entity or retain the default classification, disregarded entity. We'll cover this in the next part.

Part 2: Choose a Tax Law Entity

The two most common entity choices for single-owner Businesses are:

- LLC + Disregarded Entity;

- LLC + S Corporation.

You could also choose "LLC + C Corporation" but that almost never happens. So we'll focus on the other two choices.

Most Common Approach

Here’s the most common tax entity approach for single-owner Businesses: they start out as an LLC taxed as a disregarded entity, then when they reach a point where they can pay themselves what the IRS would consider a reasonable salary and still have profits left over, they remain but an LLC but elect S corporation tax status.

A lot to unpack, but it will all make sense. Here’s some steps to walk you through the process.

First, determine your reasonable salary

Before you can determine what tax entity makes more sense between S corporation and disregarded entity, you’ll want to know what you would say the IRS would deem to be your reasonable salary.

The IRS gives you a lot of factors to consider, but in general, your reasonable pay is the “amount that a similar business would pay for the same or similar services.” In other words, determine what services you’re offering that, if you offered them to another employer, you would be paid $X for them. For example, if you run a digital marketing agency, what would another company pay you annually to be their "digital marketing associate?"

That’s your reasonable pay.

Second, depending on salary, consider being taxed as disregarded entity

Running your company taxed as an S corporation is more complex. Once you’re an S corporation, your taxes get more complex, and you have to treat yourself as an employee. Many LLCs taxed as disregarded entities can handle their own taxes.

So, it makes sense for most businesses to initially be taxed as a disregarded entity, then when it makes financial sense, convert to an S Corp.

Why? It’s all a balancing act. There’s a lot more work with S corps and the tax advantages don’t kick in for almost any business until the business is profitable. Why is that? Self-employment taxes. Here's a couple examples that will simplify this.

|

Example 1 Templeton creates and sells art on Etsy. He makes $55,000 his first year. He calculates that his reasonable salary would be $35,000/year, and his expenses are about $20,000 a year. Because Templeton would not be profitable, he wouldn't benefit from S Corp's self-employment tax relief benefits. |

Example 2 Templetina sells ID wrist bands to hospitals. Templetina makes $100,000 her first year. She calculates that her reasonable salary would be $50,000/year and her expenses are $25,000 a year. This means she turns a profit of $25,000/year. If she elected S Corp tax status, she could save approximately 15% in taxes on that $25,000 profit, or about $3,825. |

The tax savings come from the fact that the S Corp only has to pay self-employment taxes on the reasonable salary the owner pays themselves. If there are profits after all expenses and a reasonable salary has been paid, then the S Corp only pays the ordinary income tax on those profits, not the additional self-employment taxes.

If you’re not profitable (i.e., if your business’s revenue isn’t greater than your expenses, which include your reasonable salary paid), then if you elect to be an S corporation, you’ll incur more fees, probably have to hire a CPA to prepare your corporate income tax return, have to run payroll, and other tasks that wouldn’t necessarily be required if you were simply a disregarded entity.

Also if you’re not profitable, you have more opportunities to take a “loss” to offset other income from your business if you’re a disregarded entity v. being an S corp.

But if you are profitable, then S corps start to make more sense. Some CPAs estimate that if you’re self-employed and your business generates $100,000 in revenue, then S Corp election makes sense. Otherwise, remaining as the default (disregarded entity) is often wiser.

Third, an important takeaway

Lastly, you should know that you can always convert your LLC taxed as a disregarded entity into an LLC taxed as an S corporation later. Many businesses starting off just want to get things running, aren’t sure how profitable they’ll be, and want to do whatever is simplest to start.

Then, after a year or two (if ever), if they become profitable, businesses can follow the S Corp election process for the following tax year. You can elect to begin being taxed as an S corporation in any year after you start your business, although there are deadlines for when you have to make the election in order for it to be effective in any given year.

You can also get additional tips using Legal GPS for Business.

Step 5: Choose One State to Form your LLC or Corporation.

You have to pick one state initially to file your LLC or corporation formation documents in. This is your organizing state. We'll walk you through step-by-step to help you determine which state is best.

First determine if your home state is the right choice. For most, it is.

If your business is physically located in one state, your home state, and conducts business mostly in that state, it likely makes sense to file in that state. If you don’t do that, you could end up having to pay two sets of fees rather than just one.

|

Example Let’s say you’re a graphic design freelancer now and have a tech idea to do something like automate the animation of logos. And for that company you might seek investment and pay equity compensation. Odds are you’ll start your freelance business first (the “Small Business”) and then form a separate entity for your Startup idea. |

Worse, often the fees to register your business as a “foreign entity” in your home state are the same or higher than registering your LLC in your home state.

For example, if you live and work in Georgia and decided to form an LLC in Delaware, you would need to pay $90 in fees to organize in Delaware, pay annual fees in Delaware, pay for a registered agent in Delaware, and pay $225 to Georgia to register as a foreign LLC.

Compare this to if you registered in Georgia (no Delaware registration), where you would pay $100 to register your LLC plus your annual fee ($50, for both domestic and foreign LLCs).

Or, if you live and work in Missouri and decided to form an LLC in Delaware, you’ll have the same fees in Delaware, and then have to pay $105 to file a foreign registration in Missouri. Compare this to if you registered in only Missouri, where you would pay $50 once, not have to pay Delaware fees initially, and not have to pay ongoing fees because Missouri doesn’t require annual reporting for LLCs.

Identify your home state by asking the following questions:

- Where do you physically live?

- Where do your employees physically live?

- Does your business have real estate in any particular state?

- Where is most of your business transacted?

- Where do the other owners/members of the LLC physically live?

The state you’ve identified here for some or most of these questions is probably your home state.

Next, See if the “privacy” and “asset protection” exceptions apply.

The two biggest exceptions are if you need absolute privacy (i.e., you don’t want anyone to know you own the LLC) or if you want to take extraordinary measures for asset protection and you’re a single-member LLC. This is very rare, so unless this sounds immediately pertinent to your scenario, it usually doesn’t make sense.

But in the event that one of the issues applies, you should consider forming your LLC in Delaware, Nevada, or Wyoming. These states give you the ability to be completely anonymous with your ownership of the LLC. And they have additional asset protection laws (without getting into the weeds, they ensure something called a “charging order” is available for single-member LLCs).

Ask yourself: Will you be doing business in many states or have plans to scale nationally?

If you’re a business with plans to scale nationally, or seek investors, first you should consider whether an LLC is the right choice. If it still is the choice, then Delaware, Nevada, and Wyoming might be good choices.

If one of these exceptions apply, then it’s smart to consult with an attorney to get fact-specific advice.

Lastly, Don’t fall for the “tax trap”—you won’t save on income taxes by forming in other states.

A common misconception is that if you set up a Delaware LLC or corporation (or Nevada or Wyoming LLC), you won’t have to pay corporate income taxes. While LLCs generally don’t have to pay anything related to corporate tax, even if they did, their taxes are determined by where they’re doing business, not the state they formed their LLC in. In other words, it's your home state that most likely determines what your taxes will be.

Here are some more examples:

|

Example 1 A boutique shop that mainly sells in one state would probably want to register in that state. They’ll avoid the additional fees and paperwork that go along with the foreign state registration. |

|

Example 2 A startup that plans to operate both in their home state and a handful (or more) of other states may want to consider registering in a state other than their home state. See our guide on the best states and tax benefits for startups. You should almost always be a Delaware corporation (as opposed to an LLC). |

|

Example 3 Internet-based businesses (that don’t want to raise venture capital, have investors, or sell shares) are generally best served by filing in their home state. The reason for this is simply that a smaller, internet-based business is similar to a boutique shop when it comes to LLC registration. |

Besides these examples, factor in the other points raised (e.g. privacy issues) and determine the best state to file your LLC.

For further guidance, or to understand specific state requirements, see your state’s Secretary of State website or conduct a search for “[Name of State] LLC requirements.”

Do You Need a Lawyer to Form an LLC?

The biggest question now is, "Do you need a lawyer to help you form an LLC?" For most businesses and in most cases, you don't need a lawyer to start your business. Instead, many business owners rely on Legal GPS Pro to help with legal issues. Legal GPS Pro is your All-in-One Legal Toolkit for Businesses.

Developed by top startup attorneys, Pro gives you access to 100+ expertly crafted templates including operating agreements, NDAs, and service agreements, and an interactive platform. All designed to protect your company and set it up for lasting success.

Legal GPS Subscription

Protect your business with our complete legal subscription service, designed by top startup attorneys.

- ✅ Complete Legal Toolkit

- ✅ 100+ Editable Contracts

- ✅ Affordable Legal Guidance

- ✅ Custom Legal Status Report

Legal GPS Pro: All-in-One Legal Toolkit

100+ legal templates, guides, and expert advice to protect your business.

Trusted by 1000+ businesses

Table of Contents